Vertegaal, R. (1999). The gaze groupware system: mediating joint attention in multiparty communication and collaboration. In CHI ’99: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, pages 294–301, New York, NY, USA. ACM Press. [url]

———

This paper argues that designing mediated systems is a problem of conveying the least redundant cues first. The central issue of supporting collaborative work at distance is that regardless of whether audio or video is used one should provide simple and effective means of capturing and methaphorically representing the attention participants have for one another and their work.

The authors quore Short et al.’s Social Presence Theory (1976), according to which communication media are ranked according to the degree to which participants feel co-located, and does suggest that the amount of social presence is improved by increasing the number of cues conveyed. However, when cues are redundantly coded, we can no longer predict the effects of a communication system. The authors concludes that we should avoid trying to improve communication by means of increasing bandwidth.

The authors concentrate on the problems of mediating multiparty communication, showing examples of how multiparty communication using video conferencing is not necessarily easier to manage than using telephony. Single-camera video systems do not comvey deictic visual references to objects or persons.

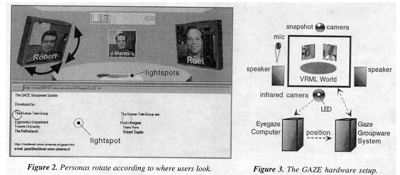

To overcome most of the limitations of previous approaches, the authors implemented a virtual meeting room where each the camera feed of each participant is represented in a moving panel that replicates the movements of the head of the real participant. This plus a lightspot on the shared workspace gives a sense of gazing at other participants and gazing at the objects used during the interaction.

The system is here described in great details but was no evaluation was reported. The paper conains also a graat review of studies showing the effect of conveying gaze direction in collaborative work.

![]() Tags: Computer Supported Collaborative Work, eye-tracking, human communication, human computer interaction

Tags: Computer Supported Collaborative Work, eye-tracking, human communication, human computer interaction