Golledge, R. G. Theories and Methods of Spatio-Temporal Reasoning in Geographical Space, vol. 639 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, 1992, ch. Do People Understand Spatial Concepts: The Case of First-Order Primitives, pp. 3–21. [pdf]

———

The author hypothetize in this paper that most individuals develop only a “common sense” configurational understanding of spatial phenomena, which accounts for incomplete and fuzzy cognitive representations of environments, and partly accounts for many spatially irrational behaviors. The author explain how human possess different degrees of spatial abilities like the ability to think geometrically, the ability to image complex spatial relations, the ability to recognize spatial patterns, etc, all of which are task dependent. Reading a map requires skills in symbol identification and orientation.

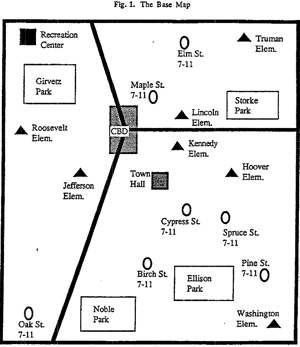

The paper reports an experiment where the author wished to find out if people become aware of functional distributions (e.g., shops, schools) and their spatial properties when asked to learn about an environment.

Results shows that even simple first order geographic primitives such as the idea of pair proximity or nearest neighbor, is not necessarily well understood in the complex map situation tested. More in details, the two distributions were not regarded as being similar, and that even performing common tasks on each distribution produced significant differtent results. No difference even between geographers and non-geographers.

One reason for a lack of good performance on the cue location reproduction task for example might be that people regionalized the initial map and that this interfered with their ability to comprehend the functional distribution as a single entry.